U-M programs and partnerships support research to reshape maternity care in Ghana

Collaborative research connected Veronica Dzomeku to the University of Michigan School of Nursing before she ever set foot on campus. When she arrived in Ann Arbor in 2017 to join the U-M African Presidential Scholars Program (UMAPS), that connection grew stronger. The program and Dzomeku’s partnerships with School of Nursing faculty have helped energize research that is reshaping midwifery practice in her home of Kumasi, Ghana, supported by an Emerging Leader Award from the National Institutes of Health’s Fogarty International Center.

Collaborative research connected Veronica Dzomeku to the University of Michigan School of Nursing before she ever set foot on campus. When she arrived in Ann Arbor in 2017 to join the U-M African Presidential Scholars Program (UMAPS), that connection grew stronger. The program and Dzomeku’s partnerships with School of Nursing faculty have helped energize research that is reshaping midwifery practice in her home of Kumasi, Ghana, supported by an Emerging Leader Award from the National Institutes of Health’s Fogarty International Center.

A UMAPS Scholar

Dzomeku was a respected nurse scientist well before she came to Michigan. A senior lecturer in the Department of Nursing at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science, she holds a Ph.D. from the School of Nursing at the University of the Western Cape in South Africa, as well as a master’s in nursing and bachelor’s in nursing and psychology from the University of Ghana. She joined the 2017-18 cohort of UMAPS scholars to build her scientific skill set and gain new insight that could inform her research in Kumasi.

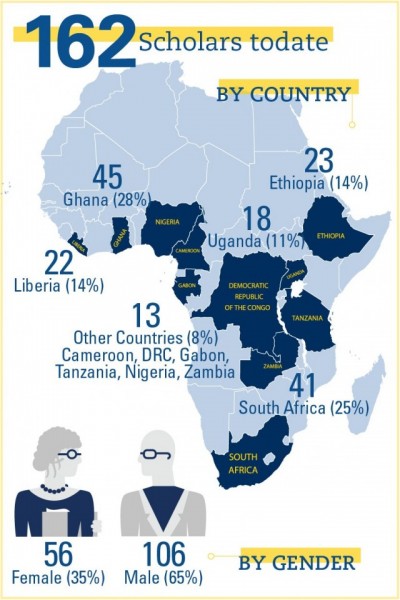

UMAPS brings early career faculty from African universities to Ann Arbor, where they are paired with a faculty collaborator and granted full access to the university’s resources to further their work on a research project, academic degree, publication, grant proposal or other activity. The program aims to support the next generation of African scholars by integrating them into international academic networks while fostering the university’s international research collaborations across disciplines.

As a UMAPS scholar, Dzomeku worked with Professor and Associate Dean for Global Affairs Jody Lori, Ph.D., CNM, FACNM, FAAN. The two had previously partnered on studies exploring the experiences of women receiving childbirth care at public health facilities in Ghana as well as barriers preventing the placement of midwifery students in rural communities. In Ann Arbor, Dzomeku worked with Lori to push new projects forward, strengthen her writing skills and devote more time to time management.

“For years, I felt like I never had enough time to develop these skills, and I never had a formal mentor, so this was an important learning opportunity for me,” Dzomeku said. “Those who thought through the UMAPS idea hit the nail on the head. Coming to Michigan and working with Jody was a life-changing experience, and it really was the beginning of my academic career.”

The UMAPS experience has also had a ripple effect on Dzomeku’s students, patients and community.

“The effects of that exposure extend to our students who are providing direct care. At every level, it’s making an impact and inspiring a conscious effort to mentor others,” she explained.

In 2018, Dzomeku returned to Kumasi to lead a re-energized approach to research she began during her Ph.D. studies — a project with tremendous potential that’s now supported by the prestigious Fogarty award.

An emerging leader

An emerging leader

Dzomeku’s project, “Changing the Culture of Disrespect and Abuse in Maternity Care in Kumasi, Ghana,” was based on observations and experiences from her work as a practicing nurse-midwife.

The training focuses on four modules, beginning with communication skills and respectful and dignified care.

“These modules are about developing soft skills for midwives,” Dzomeku said. “Many of our clients have complained that they didn't feel respected during the provision of their care, so we have been training midwives on it, and the feedback we’ve received has been great.”

The third module addresses antenatal care, with training that allows patients to spend less time waiting to receive direct care by grouping women who are in the same trimester. In these groups, Dzomeku explained, women can learn from shared experiences. The process can ultimately optimize the care and education midwives provide to better address women’s specific needs.

“The quality of time spent in the hospital becomes useful, as opposed to the traditional method where you have a woman who is 10 weeks pregnant and another who is 35 weeks pregnant all waiting together to see one midwife,” Dzomeku said. “Sometimes women were waiting for over five hours to see a midwife for less than five minutes. They felt like coming to the clinic was a colossal waste of time.”

The fourth module centers on birth positions. Dzomeku noted that in most Ghanaian hospitals, women are only allowed to deliver in a supine position, creating discomfort, countering best practices and contributing to the prevalence of home births.

“Women found that very uncomfortable, and they were not satisfied with it,” said Dzomeku. “For some of them, that’s why they chose to deliver at home, because they are allowed to deliver in other positions such as standing, kneeling or squatting, which research shows are more effective.”

The steps in Dzomeku’s training program could prove critical to reducing Ghana’s high infant and maternal mortality rates by leading more women to move away from home delivery in an unskilled setting.

“I have firsthand experience from my practice that suggests women will sometimes come to the antenatal clinic but decide to give birth at home,” Dzomeku said. “Most of the complications that lead to mortality occur around the time of birth. In Ghana, home delivery is unskilled, so we always advise women not to deliver at home.”

At a teaching hospital in Kumasi, Dzomeku began her project by training 15 midwives who have gone on to serve as trainers themselves. So far, more than 100 midwives have been trained through her model. Now, Dzomeku is organizing studies focused on the midwives themselves, hoping to gain a better understanding of their expectations and experiences before and after training.

“We’ve received good reports so far, and they’ve recommended we train midwives at other facilities in Ghana as well,” she said. “They also want to go beyond midwives to train every staff member within the hospital so everyone can understand what respectful maternity care is all about.”

Dzomeku, Lori and other collaborators have co-authored a number of papers detailing the findings of their work, with more currently under review. The Fogarty Emerging Leader Award runs through 2025, and Dzomeku is looking forward to expanding her training program while pursuing new directions for research that has already made a significant impact in her community. In January 2021, Dzomeku was awarded a highly competitive grant from the U.S. Agency for International Development's Partnerships for Enhanced Engagement and Research Program for her project, "Community and Hospital-based Obstetrics WhatsApp Triage, Referral, and Transfer (WAT-RT) System."

Explore publications related to this work:

- “’I wouldn’t have hit you, but you would have killed your baby:’ exploring midwives’ perspectives on disrespect and abusive care in Ghana”

- “Determinants of satisfactory facility-based care for women during childbirth in Kumasi, Ghana”

- “Exploration of mothers’ expectations of care during childbirth in public health centers in Kumasi, Ghana”

- “Exploring midwives’ understanding of respectful maternal care in Kumasi, Ghana: qualitative inquiry”

- “Developing a tool for measuring postpartum women's experiences of respectful maternity care at a tertiary hospital in Kumasi, Ghana”

All Infographics courtesy of U-M African Studies Center (LSA).