Ensuring protection for the front lines

Written by: Alex Bienkowski

The COVID-19 pandemic has tested America’s health care workforce unlike any crisis in recent history. Nearly 600 U.S. health workers and counting have died of COVID-19, and a shocking shortage of personal protective equipment has likely contributed to those losses.

In the early stages of the U.S. outbreak, Elizabeth Tone Hosmer Professor of Nursing Chris Friese, Ph.D., RN, AOCN®, FAAN, reconvened with six colleagues from the 2018 National Academy of Medicine Study Committee on the Use of Elastomeric Respirators in Health Care to issue an urgent plan of action. Their publication, “Respiratory Protection Considerations for Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” outlined crucial steps the country must take to provide evidence-based respiratory protection to health care workers.

No time to waste

Friese and his colleagues explained that the well-being of the U.S. health care workforce has a direct impact on the nation's health, security and economic prosperity. To account for early missteps and offer a new path forward, the group detailed three immediate actions and four long-term strategies that could guide a more effective effort to protect health care workers from COVID-19 and future pandemics.

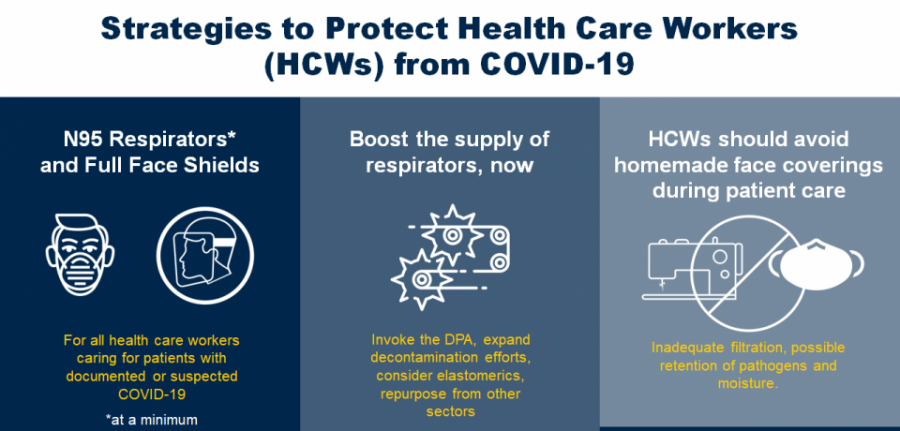

“1. At a minimum, health care workers delivering care to patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 should wear N95 respirators and full-face shields.”

Unlike a standard surgical mask, the N95 can drastically reduce exposure to harmful airborne particles, including the respiratory droplets that serve as the primary mode of transmission for COVID-19.

“We have to put the highest quality respiratory protection in the hands of health care workers who are in the highest risk settings like the ICU and ER,” Friese said.

Hospitals in communities that were hit hardest by the initial outbreak quickly reported shortages of N95s and other personal protective equipment. Improving the rapidly deteriorating supply of respiratory protection was the authors’ next crucial recommendation.

“2. Boost and protect the supply of N95 respirators for health care workers under the current crisis standard of care scenario.”

In this multifaceted strategy, the group emphasized the importance of expanding research efforts to decontaminate used N95 respirators. Recently, the Food and Drug Administration has reissued emergency use authorizations revising which respirators can be decontaminated for reuse as an urgent measure.

“Several science teams have published protocols that show promise, and many large health systems have now formed their own teams to conduct this work,” Friese explained. “Teams are examining heat, ultraviolet light and hydrogen peroxide vapors, but it is important to note this is a stopgap measure — N95s are not designed for reuse.”

The group also highlighted the need to augment the supply of N95s with resources from other industries. Reusable elastomeric respirators, which are commonly used in construction work and industrial settings, can offer equally effective protection.

“We have observed health systems procuring their own supplies from other sectors,” said Friese. “To me, a respirator that meets N95 standards, even if not originally approved for health care settings, is better than other approaches when caring for patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infections.”

Next, Friese and his colleagues reinforced what many health and policy experts had acknowledged since the first signs of community spread appeared in the United States: The president should exercise full authorities under the Defense Production Act (DPA) to produce and distribute N95 masks and other protective equipment.

“The details are unclear, but it does not appear the DPA has been used to its full extent for this public health emergency,” he said. “There are concerns for additional waves of COVID-19 outbreaks, and flu season is fast approaching. I remain concerned that we will not have an adequate supply of respiratory protection for this pandemic and future airborne transmissible diseases.”

In many cases, individual states and health systems have been left to fend for themselves.

“That’s unfortunate, because instead of procuring a steady pipeline of N95s, we now have internal competition along with unclear inventories and real-time demand,” said Friese. “This is indeed a missed opportunity.”

The group’s last urgent recommendation was a word of warning:

“3. Homemade facial coverings offer no protection for health care workers.”

While cloth face coverings have been widely adopted by the general public, they deliver nearly no protection from COVID-19 transmission in the health care setting. As emerging reports revealed a severe shortage of respiratory protective equipment for nurses and other frontline workers, the authors noted that homemade masks, including bandanas and scarves, are “woefully inadequate because of concerns for moisture and pathogen retention."

Planning ahead

Three immediate strategies could help make up for precious time lost, but additional measures outlined by Friese and his counterparts can significantly improve preparedness for new surges of COVID-19 and future pandemics.

“1. Substantial funding to develop and test better personal protective equipment specific to health care settings and ascertain exposure levels across settings and clinical procedures.”

Since the H1N1 outbreak in 2009, Friese noted, government and scientific agencies have documented the need for better protective equipment to face emerging public health crises. Funding efforts to determine what equipment is needed in different settings and circumstances could make a decisive impact on pandemic preparedness. Unfortunately, that funding hasn’t emerged.

“Funding for this kind of work usually happens after the public health emergency has already hit the community,” he said. “In some ways, it’s almost too late for us to integrate the findings into responding to the current pandemic. It is essential to study these questions with the care and deliberation good science takes so we are better prepared next time.”

“2. Reinvest in, monitor and replenish the Strategic National Stockpile. Integrate these efforts with a reinvigorated Hospital Preparedness Program.”

“One of the challenges our committee noted is that a great deal of information about the stockpile is classified,” said Friese. “This makes sense on some level. However, there are some basic data elements that could be shared with the community so that health systems and public health agencies can plan ahead.”

The ability to learn from recent mistakes will prove critical. Replenishing the depleted federal supply of protective equipment could prevent recurring instances of unhealthy competition for lifesaving resources.

“Health systems, public health officials and governors were compelled to explore alternatives to the stockpile,” Friese said. “It is disappointing that when our nation needed the stockpile the most, the resources weren’t there. The fact that we do not have adequate personal protective equipment, specifically adequate respiratory protection, is a national disgrace.”

“3. Develop state-based data systems to track real-time demand and supply for essential health care equipment during surge situations.”

Real-time reporting nationwide can help anticipate emerging crises and direct resources where they’re needed most.

“Every state collects this information differently, but some don’t report it or share it,” Friese said. “The result is that some facilities sit idle with ventilators, equipment and staff while you have other hospitals using one ventilator for two patients, calling up retired doctors and nurses, and nurses wearing trash bags to work.”

Beyond tracking supply and demand in health care settings, the group highlighted the importance of understanding the health of the workforce itself. National tracking could yield tremendous benefits, but discrepancies in policy and information sharing present complications that inhibit an informed response.

Today, our e-pub is posted that outlines crucial actions the US must undertake to provide evidence-based respiratory protection to health care workers (HCWs) during #COVID-19. ![]()

As a model for this effort, Friese pointed to Michigan Medicine.

“One of the many things I have appreciated about our health system’s response is they share the data they are permitted to share transparently,” he said. “That benefits staff and the community. Employees were able to see the trend in cases and the positive cases among health care workers. We used that data to inform some risk prevention strategies.”

The availability of information varies across systems and states. While Ohio has tracked and reported COVID-19 cases among health workers, many states and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention do not report them. This inconsistency is problematic for two reasons:

“First, if we can’t estimate illness among health care workers, our projections of available staff to support clinical operations is compromised. Second, if we did track cases, I expect that health care work would be one of the most predictive factors in COVID-19 incidence.”

Friese believes this lack of transparency not only leaves the country ill-equipped but is an affront to those on the front lines.

“It’s an insult to health care workers and other first responders who have risked their own safety to care for patients during these uncertain times,” he said. “It’s an insult to the memories of those we lost that we can’t even honor them properly.”

In fact, Friese has worked with journalists at Kaiser Health News and The Guardian to help their efforts tracking cases and deaths among U.S. health care workers.

Continued challenges and optimistic outcomes

The strategies outlined in the group’s publication can help protect the estimated 18 million U.S. health care workers, but COVID-19 has put a spotlight on many new and longstanding challenges.

“In the U.S., we have lost too many people of color, older adults, health care workers and first responders,” Friese said. “The economic devastation continues to mount. Assisted living and skilled nursing facilities, prisons and certain work settings were especially unprepared and hard hit.”

While the pandemic has brought many problems to the forefront of the national consciousness, Friese knows it’s also revealed a number of reasons to remain optimistic:

- Social distancing can (and has) saved lives.

“In general, communities saw the merit in social and physical distancing, and where they adopted those approaches well, lives were saved.”

- Community action can make a meaningful difference.

“I was heartened to see community members respond to shortages of PPE and donate supplies and equipment to their local health systems. To me, that was the ‘Dunkirk’ moment of this pandemic. I hope we can channel that solidarity in future crises.”

- The pandemic has made us address harsh realities.

“We painfully witnessed how communities of color lost more members than white communities. That raises the obligation and opportunity for us to do more for these populations, including relevant basic, clinical and social science to develop solutions that promote equity and justice.”

- Greater connection and collaboration among the global scientific community.

“In general, social media and more connections across scientific communities accelerated progress. The pace at which relevant science has emerged will hopefully shorten the time to population-level prevention through a vaccine.

“We witnessed rapid sharing of clinical approaches across the globe, including fairly simple things like how ICU teams care for patients to minimize the time and number of workers exposed. We learned a lot from the experiences of intensive care units in Italy. We are now starting to see health systems and public health agencies share screening and treatment protocols via social media.”

- Health care adaptations can lead to lasting change.

“We learned rapidly that not every health care encounter needs to be in person. I expect telemedicine and virtual health approaches to survive past this pandemic, so long as we determine how to deliver such encounters safely, equitably and efficiently.”

Putting new knowledge to work

Many states are seeing new spikes in COVID-19 infections and deaths. To avoid repeating mistakes, leaders from health systems to the halls of Congress will have to make decisive actions backed by the knowledge gained in recent months.

“I hope that the public health officials and health system leaders will codify what we have learned from this pandemic,” Friese said. “Pay attention to the stockpile. Make sure you train routinely for the unexpected. Put health care worker and first responder safety as a priority. Build better data systems to share information in real time across sectors and government agencies. And improve public health and crisis communication strategies.”

For nurses, many of whom were forced to adapt to circumstances they never expected, those experiences can be prove valuable now and into the future.

“Nurses who never wanted to work in acute care suddenly found themselves managing very sick patients or assuming new roles,” Friese acknowledged. “In future infectious outbreaks, monitor the peer-reviewed literature and official guidance to understand routes of transmission, risk factors and preventive strategies. Information will change over the course of a pandemic, but updated knowledge may be the best defense.”

Friese understands that for many health care workers, their guard may never go back down. But practicing self-care and staying connected can carry special significance in the days, months and years ahead.

“It’s OK to take time for yourselves and your loved ones,” he said. “This work can be exhausting and unpredictable. Regular exercise, safely connecting with others and reflective practices can build resilience and support us during this pandemic and beyond.”

The future of nursing depends on world-class education and research. In this uncertain time, you can provide critical support to the U-M School of Nursing by making a gift to support innovative research endeavors.