We Dare to Shape the Future

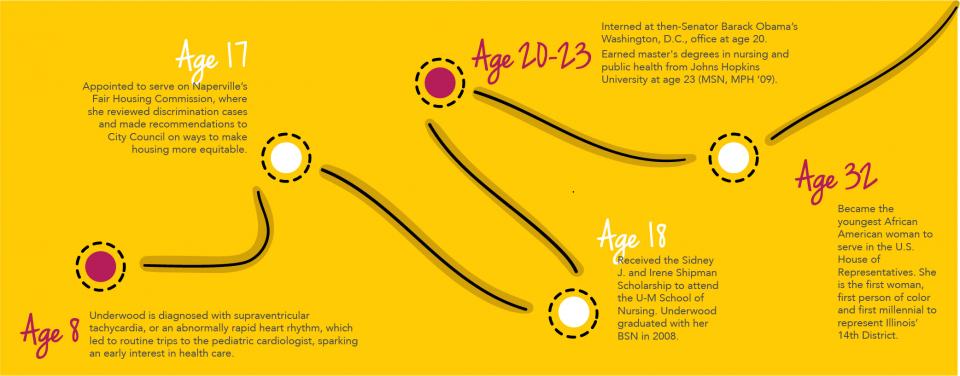

For Lauren Underwood (BSN ’08), health care and politics were always part of the same conversation. At 33, she is the youngest African American woman to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives. She is the first woman, first person of color and first millennial to represent Illinois’ 14th District. She’s been called a rising star in the Democratic Party and was recently listed on Time magazine’s “100 Next” list of influential people who are shaping the future. But at the heart of it all, Lauren Underwood is a nurse.

The politics of the profession

In fall 2018, Underwood defeated a four-term incumbent to win the congressional seat in the reliably Republican 14th District. She realizes not every nurse aspires to a career in politics, but she also knows that being apolitical is impossible.

“Everything we’re doing is political,” Underwood said. “For the advanced practice nurse, their license and ability to prescribe is dictated by our political structure. For the RN who works at a community clinic, what happens if that federally qualified health center loses its funding? We don’t just get to opt out. Patients trust us, and that comes with the responsibility to do everything we can to ensure the systems they depend on give them a chance to live their best lives.”

On the campaign trail and now in office, much of her work is grounded in one of nursing’s foundational principles: Health care is a human right.

“We shouldn’t have to have conversations with constituents that talk about ‘heat or health care’ in the winter. We shouldn’t have seniors on a fixed income who can’t afford anything because they’re trying to take their medication as prescribed. And we shouldn’t have sick kids worrying about their parents’ ability to afford their insulin,” Underwood said.

For many nurses, those conversations have crept into the clinical setting.

“There are nurses who now have to spend more time talking about cost and affordability than they do about strategies to improve their patients’ health — that’s not acceptable.“

A vision to serve

Underwood grew up in Naperville, a western suburb of Chicago. As a child, she was diagnosed with supraventricular tachycardia, or an abnormally rapid heart rhythm. Routine trips to the pediatric cardiologist sparked an early interest in health care, which converged with a burgeoning passion for public service in high school.

At 16, she was appointed to serve on Naperville’s Fair Housing Commission, where she reviewed discrimination cases and made recommendations to City Council on ways to make housing more equitable in the upper-middle-class community.

“I wanted to make sure that our community was as welcoming as we professed it to be,” she said. “I was curious, opinionated, and I loved the opportunity.”

She served a second term on the commission her senior year before receiving the Sidney J. and Irene Shipman Scholarship to attend the U-M School of Nursing. Underwood was excited to enter the field but struggled to see a career path that could combine her interests in health care and public policy. “Maybe I could testify at city council one day,” she thought. Then an early morning class her first year on campus changed everything.

From Ann Arbor to Capitol Hill

Policy and Politics in Nursing and Health Care met on Mondays at 8 a.m., and while sleepy classmates second-guessed their schedules, Underwood couldn’t wait to get started.

“I think I was the only one excited about it, but that class changed my life,” she said. “To be introduced to something that would combine my interests that early in my education was transformational. I had no idea that a nurse could spend their career focusing on policy to improve the well-being of communities and populations.”

“She came in with a vision to make a difference through policy, which is rare for undergraduates,” said Professor Emerita Barbara Guthrie, who co-taught the course with former U-M School of Nursing Dean Ada Sue Hinshaw. “Lauren wanted to understand how policy could keep people out of the hospital. She was always asking questions and seeking out new information and experiences. I think she was born to do this work.”

With focused ambition, Underwood capitalized on opportunities to position herself for a career as a policy nurse, including a summer internship at then-Senator Barack Obama’s Washington, D.C., office. On campus, she became a leading voice on the University Health Services Advisory Board and adjusted her curriculum to better align with her goals.

“The idea of health care policymaking was no longer theoretical,” she said. “I wanted to develop a diverse skill set, and the nursing faculty helped me cultivate that.”

It’s easy to draw a line from Underwood’s experiences at Michigan to the work she’s doing in Congress. Last spring, she co-founded the Black Maternal Health Caucus to improve outcomes for a population that experiences one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the world. During her senior year at U-M, Underwood worked with Professor Antonia Villarruel on interdisciplinary research to reduce the risk of low birth weight and increase access to prenatal care for women in Detroit.

“You can’t work on policy without hearing from those you’re trying to impact, and I could tell Lauren was serious,” said Villarruel, who is now dean of the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing. “I think that work helped her understand some different perspectives and approaches. I’m so proud of the person she’s become. The way she speaks about evidence-based policy and her willingness to hear from every constituent … that is all nursing.”

After earning master’s degrees in nursing and public health from Johns Hopkins University in 2009, Underwood returned to Washington, D.C., to work for the Department of Health and Human Services, where she helped implement the Affordable Care Act and prepare communities for public health emergencies such as the Ebola outbreak, Zika virus and Flint water crisis. She left government for a brief period in 2016 before launching the underdog campaign that would lead her right back to the nation’s capital.

Underwood enters 2020 vying for re-election to build on the work she’s prepared for her whole life. She is a passionate public servant, an unexpected incumbent and a proud Michigan Wolverine. But above all else, she is a nurse.

“When people ask me what I do, I say that I’m a nurse,” Underwood said. “That is part of my identity, and I love the career that I’ve had in this profession.”